In a recent article, I suggestedthat batteries might replace oil for many of our transportation needs within two decades. Batteries store energy, and we need a way to produce that energy in the form of electricity. Currently we produce most of our electricity from natural gas and coal. And while our use of natural gas and coal doesn’t feed the coffers of unsavory regimes like Russia and Saudi Arabia the way our use of oil does, it’s still the case that these energy sources are limited. They run out. What will replace them?

The leading candidate is solar power. Cost is droppinglike a rock, including “balance of system” costs that include things like installation and land. For an update on the status of solar power, see this excellent article from The Economist. Of course, improvements in battery storage are very helpful for solar, since you need to store some energy for nighttime.

But there is still a strong contingent out there who is dead-set against the solar revolution – not because they want to keep using fossil fuels, but because they are convinced that only nuclear power can solve our energy crunch.

One example of this faction is the Breakthrough Institute, which regularly releases articlescomparing nuclear and solar, invariably supporting the former over the latter. Of course, solar costs continue to perform much, much better than they predict, but they continue to insist that nuclear – and only nuclear – must be the energy source of the future.

I’m always a bit puzzled by the anti-solar antipathy of the pro-nuclear crowd. Energy is energy, after all. Perhaps nuclear looks muscular and futuristic – an emblem of national greatness – while solar looks like wimpy hippie stuff.

But regardless of people’s feelings, the fact is that conventional nuclear power – by which I mean uranium fission, the kind of thing Mr. Burns produces on The Simpsons – is on the way out. This is not a cry of triumph on my part, but a lament. Nuclear power is cool. It’s just not the future.

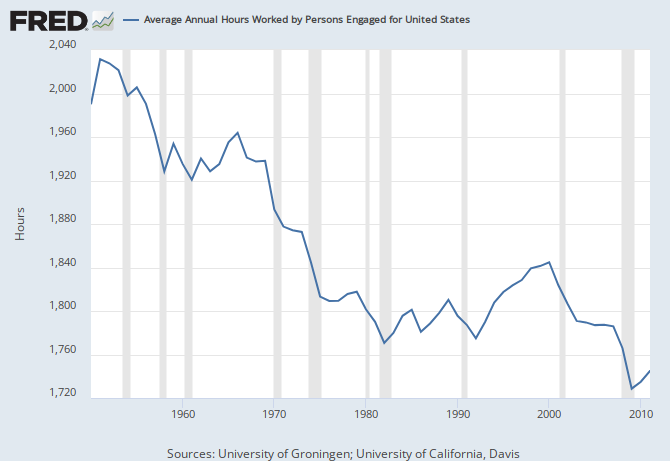

For the most convincing evidence that uranium fission is on the way out, I again point you to The Economist. Their 2012 special report, called “The Dream That Failed,” shows how nuclear usage is flat, and expected to decline in rich countries.

There are three basic reasons conventional nuclear is dead: cost, safety risk, and obsolescence risk. These factors all interact.

First, cost. Unlike solar, which can be installed in small or large batches, a nuclear plant requires an absolutely huge investment. A single nuclear plant can cost on the order of $10 billion U.S. That is a big chunk of change to plunk down on one plant. Only very large companies, like General Electric or Hitachi, can afford to make that kind of investment, and it often relies on huge loans from governments or from giant megabanks. Where solar is being installed by nimble, gritty entrepreneurs, nuclear is still forced to follow the gigantic corporatist model of the 1950s.

Second, safety risk. In 1945, the U.S. military used nuclear weapons to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but a decade later, these were thriving, bustling cities again. Contrast that with Fukushima, site of the 2011 Japanese nuclear meltdown, where whole towns are still abandoned. Or look at Chernobyl, almost three decades after its meltdown. It will be many decades before anyone lives in those places again. Nuclear accidents are very rare, but they are also very catastrophic – if one happens, you lose an entire geographical region to human habitation.

Finally, there is the risk of obsolescence. Uranium fission is a mature technology – its costs are not going to change much in the future. Alternatives, like solar, are young technologies – the continued staggering drops in the cost of solar prove it. So if you plunk down $10 billion to build a nuclear plant, thinking that solar is too expensive to compete, the situation can easily reverse in a couple of years, before you’ve recouped your massive fixed costs.

If you want to see these forces at work on the largest possible scale, look at the example of Japan. Japan was a leader in solar when the technology first emerged, but the government bet big on nuclear. Now, with nuclear power suddenly…um…radioactive following Fukushima, Japan is struggling to catch up in solar. Meanwhile, huge losses by the Japanese nuclear industry are going to land in the lap of the government and the too-big-to-fail banks.

Oops.

Uranium fission was a great idea, but it hasn’t worked out. If nuclear fission is going to be viable in the future, it’s going to require thorium fuel (which is much safer than uranium) and much smaller, cheaper reactor designs. Those technologies are still in the research stage, not ready for immediate use. Meanwhile, solar power is racing ahead much faster than anyone expected, continuing to beat all the forecasts.

Our government should continue to fund research into next-generation nuclear power. But what next-generation energy source should we be installing, right now? It’s not even a contest. Solar beats nuclear.

%2BNaoshi%2BHatori%2B(2)_WEB.jpg)

.jpg)