Here is a news article about a Malcolm Gladwell speech. This news article is of great interest to me, since it suggests that it's not actually very hard to build a lucrative career going around and giving knowledgeable-sounding speeches about concepts, technologies, or companies that are in the news. I could do that job. Dear readers, you know I could do that job.

A more minor reason that this article is of interest to me is that it gives me a chance to do a snarky point-by-point refutation, which is something I have to do periodically or else go (more) insane. So let's go through and count some of the silly things that Malcolm Gladwell is quoted in this article as having said.

Last night futurist, journalist, prognosticator, and author Malcolm Gladwell told pretty much the most data-driven marketing technologist crowd imaginable that data is not their salvation.

In fact, it could be their curse.

Bump-bump-BUMMMMM!!!

So how is data our curse?

“More data increases our confidence, not our accuracy,” [Gladwell] said at mobile marketing analytics provider Tune’s Postback 2015 event in Seattle. “I want to puncture marketers’ confidence and show you where data can’t help us.”

Except sometimes more data does increase our accuracy. For example, you can have an estimator that is asymptotically unbiased, but biased in small samples. So Gladwell is totally wrong about that.

Next, Gladwell tells us about the "Snapchat Problem":

The average person under 25 is texting more each day than the average person over 55 texts each year, Gladwell says. That’s what the data can tell us.

What it can’t tell us is why.

“The data can’t tell us the nature of the behavior,” Gladwell said. “Maybe it’s developmental … or maybe it’s generational.”

Well that particular piece of data won't tell you, but maybe others could. For example, you could use regional/national variation in the time that countries got smartphone service, and compare Snapchat uptake among age-matched cohorts.

Of course, that is a different piece of data than the one Gladwell cited. Does Gladwell think it is a significant, penetrating insight to point out that for different questions, you may need different data sets? When Gladwell calls data a "curse", is he using the word "curse" to mean "something that you might need more than one of in order to be omniscient"?

Anyway:

Anyway:

Developmental change, in Gladwell’s story, is behavior that occurs as people age...Generational change, on the other hand, is different. That’s behavior that belongs to a generation, a cohort that grows up and continues the behavior...The question is whether Snapchat-style behavior is developmental or behavioral.

“In the answer to that question is the answer to whether Snapchat will be around in 10 years,” Gladwell said.

No, that will most certainly not tell us whether Snapchat will be around in 10 years. For example, suppose Snapchat is "developmental", so that young people like it more than old people. Well, there is a constant new supply of young people. But suppose instead that Snapchat is "generational", so that people who grow up with it like it. Well, why wouldn't new generations like growing up with it just as much as old generations did? So even if we answer Gladwell's question, it does not, in fact, tell us much about the future of Snapchat.

Next, Gladwell tells us about the "Facebook Problem":

“Facebook is at the stage that the telephone was at when they thought the phone was not for gossiping — it’s in its infancy,” Gladwell said...

The diffusion of new technologies always takes longer than we would assume, Gladwell said. The first telephone exchange was launched in 1878, but only took off in the 1920s. The VCR was created in the 1960s in England, but didn’t reach its tipping point until the 1980s...

Technologies that are both innovative and complicated, like Facebook, take even longer to really emerge.

Except that this doesn't apply to Facebook, because everyone already uses Facebook. Yes, there was a period in time when social networks - Friendster, Myspace - were not widely used. That era is now in the past. People may find new ways to use Facebook, but it's not in its infancy - it has already experienced near-universal uptake. Discussing when Facebook might "really emerge" is like discussing when television might "really emerge".

Finally, Gladwell tells us about the "Airbnb Problem":

The sharing economy, featuring companies like Airbnb, Uber/Lyft, even eBay, rely on trust...

And yet, if you look at recent polls of trust and trustworthiness, people’s — and especially millennials — trust is at an all-time low. Out of ten American “institutions,” including church, Congress, the presidency, and others, millennials only trust two: the military and science...

That’s conflicting data. And what the data can’t tell us is how both can be true, Gladwell said...“So which is right? Do people not trust others, as the polls say … or are they lying to the surveys?”

So is it a contradiction if people trust the clocks on their cell phones but distrust Vladimir Putin? Is it a contradiction if people trust their neighbors but distrust the mafia? Are data contradictory whenever they show differing levels of aggregate trust in different people, institutions, or objects? And in general, why should trust in institutions be correlated with trust in other individuals?

What really startles me is that people trust Malcolm Gladwell to say useful things at marketing conferences.

Anyway, generating such jaw-dropping nonsense must get tiring, so Gladwell falls back on some good old tried-and-true incorrect facts:

[Gladwell said there has been] a massive shift in American society over the past few decades: a huge reduction in violent crime. For example, New York City had over 2,000 murders in 1990. Last year it was 300. In the same time frame, the overall violent crime index has gone down from 2,500 per 100,000 people to 500.

“That means that there is an entire generation of people growing up today not just with Internet and mobile phones … but also growing up who have never known on a personal, visceral level what crime is,” Gladwell said.

Baby boomers, who had very personal experiences of crime, were given powerful evidence that they should not trust.

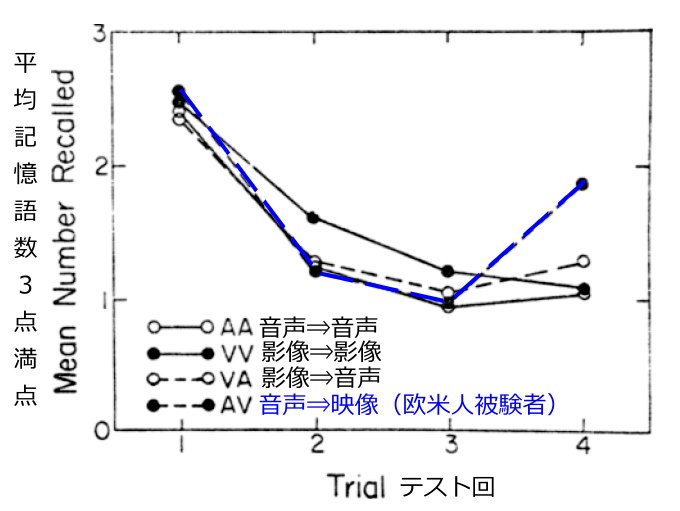

Except here is a chart of U.S. homicide rates:

You'll see that when Baby Boomers were young (under 20), there was even less homicide (and other crime) than when Millennials were under 20. Oops.

Also, Gladwell's statement that young people don't know "what crime is" ignores the fact that U.S. crime rates are still many times what they are in other countries. It's just an obviously false statement.

Also, just to be complete I should note that if Gladwell were right, regions that experienced much less of a crime spike in the 70s and 80s should have higher Airbnb use among Baby Boomers. But I think we've seen very high uptake in, say, Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, where the crime boom was much less severe. However, rigorous analysis (with yes...gasp...DATA!) would be able to answer this question more definitely.

Folks, there are many important cautions to be made about the use of Big Data. These are not they.

Folks, there are many important cautions to be made about the use of Big Data. These are not they.

And now, finally, just for fun, we have the Coup de Gladwell:

“I think millennials are very trusting,” Gladwell said. “And when they say they’re not...they’re bullshitting.”

And there you have it, folks. Who needs data when you have Gladwellian Pronouncements. The future is not the era of Big Data...it is the era of Big Gladwell.

Now if only we could put Gladwell's insight in an app and sell it...