Doutak bells are a quite mystery to me.

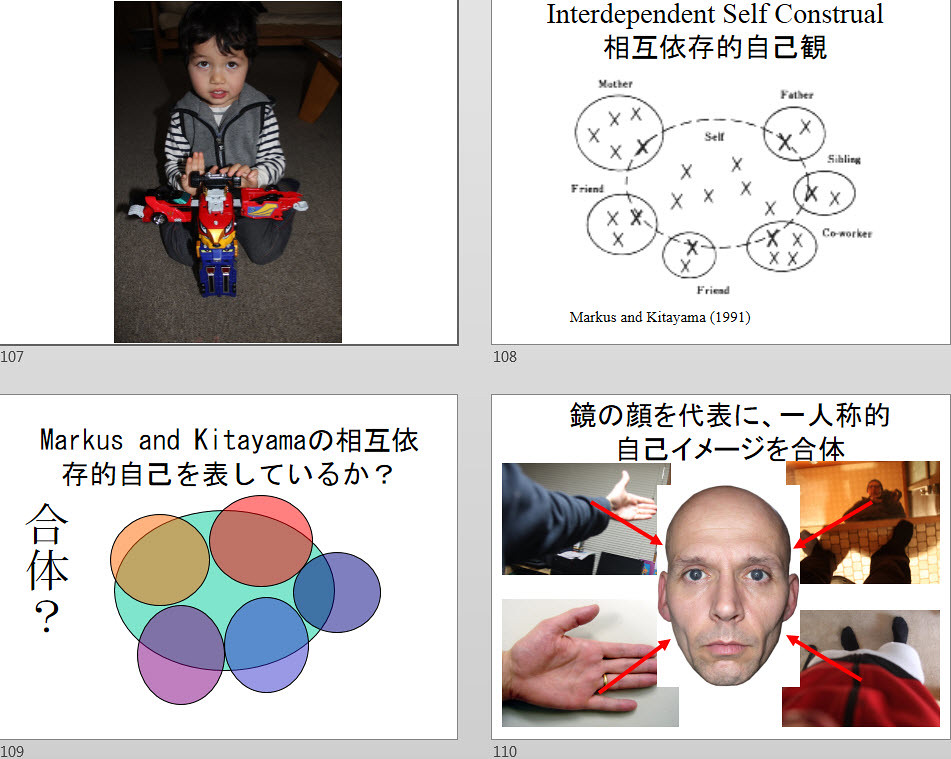

They are found dating from the Yayoi period when, I believe the previous, indigenous Japanese Joumon ("rope pattern") Japanese culture that had existed in Japan for millennia was invaded by horse mounted invaders from the continent. These bells were probably originally horse-bells, to allow horse mounted warriors to know where their horses are in the dark for instance. They started out being about the size of the bell that Ray is holding in the above photo, but were gradually made in larger and larger sizes.

My guess is that these larger and larger bells were in part to prove regal (or invader) hereditary, "My father or (great great..) grandfather was a horse mounted warrior." And with each passing generation the bells were made in larger sizes, perhaps.

The Japanese themselves have a tendency to believe that there was no "invasion" and that the Joumon people evolved into Yayoi people, and subsequently Kofun people, due to the arrival of "technology" from the continent rather than due to subjugation. The Japanese tend to believe, traditionally at least, imho, that their culture is continuous or contiguous from the year dot. And they may be right.

The genetic record however seems to point to a considerable differences (in height for instance) with at the same time much overlap, so at least there was interbreeding between an indigenous and arriving race. On the other hand, I suppose that genes might also be described as a "technology," and Japanese culture may have survived changes to the gene pool. I think it very likely.

I imagine Yayoi warriors arriving and breeding (no offence intended) with the indigenous

Joumon people, and then later a second wave of invaders (related to the first) arriving in the Kofun (ancient burial mound) period. This two wave hypothesis is suggested by some (Korean) historical interpretations of Japanese mythology. After the latter wave vast tombs were created. The creation of vast tombs, all around Japan, makes me think that there was great stratification within society. I imagine that those that were related to the invaders rounded up and forced vast numbers of indigenous and mulatto stock Japanese and had them build tombs the size of the Egyptian pyramids for their new masters. But this is all my imagination. Korean and Western historians tend to present a sort of "Japan was invaded" type of history, whereas, as I say, the Japanese tend to portray their history as one of continuous evolution with changes in society being attributed to the arrival of new technologies such as for rice farming. I guess that the difference in historical outlook is one of degree. The Japanese are, and their culture is, great at maintaining continuity, of which a great deal remains. This post is about the possibility of continuity between doutaku (as held by my son Ray) and dogu (pictured above right).

Returning to the dotaku bells, they have peculiar characteristics. They appear to have been kept, while not in use, buried in the ground, being unearthed at specific occasions. One theory has it that they were buried in order to soak up and be replenished with the spirit of the earth. The bells often have pictorial inscriptions that may be rebuses, punning on that which they represent. They seem to have a lot of water related imagery and a preponderance of images of deer.

Ah yes, I remember now (I make the same observations over and over again): it seems to me that these doutaku bells may be the origin of the temple bells that are used to ring in the new year in Japan in the "joya no kane" (

除夜の鐘) ritual, which are even more massive than the largest doutak. They look similar. They are likewise inscribed. These "joya no kane" bells are now associated with Buddhist ritual to purify the ringers of sins, of which there are said to be 108.

The "rope pattern",

Joumon culture indigenous Japanese, who existed for millennia, seem to have created first person body view (

McDermott, 1996) figurines or

dogū (土偶) which have similarities with the Venus figurines found all over the palaeolithic world. These figurines in Japan were often destroyed. I wonder if they were destroyed (and perhaps buried) in an attempt to exorcise their owners from the mother that occupied their, and perhaps all our, minds.

If so then, by a vast leap of conjecture, it might be argued that the practice of making first person body view figurines and then breaking and burying them, may have evolved into the practice of making vast bells and ringing then (at first) burying them.

This conjecture parallels the hypothesis of Lacanian (and Freudian but less explicitly) psychology which has it that the self evolves by first being represented visually as a body view, then narrativally in phonemes.

In each stage the self is paired with an other-of-the-self that witnesses the self representation.

Lacanian psychology seems to lack reference to self-person body views. The visual or "mirror-stage" is purported to be one in which the the mirror self, or third person body image such as represented in mirrors, and the form of other children with whom infants identify, is seen from the perspective of real others and is therefore groupist, and interpersonal, rather than intra-psychic (in the mind).

It is only, according to Lacan and Mead, with the arrival of language that humans internalise an imaginary friend or Other or ear (of the Other). In Lacan and Mead, and Western philosophers in general, ears are argued to be internalisable but eyes are not. They claim that one can speak, whisper and eventually "think" in words to "oneself," or rather that hidden friend, a generalised other, super ego, super addressee. Eyes are always, interpersonal, groupist, social, out there in the world.

Till the discovery of mirror neurons, our paper on Mirrors in the Head, McDermott's first person, Nishida's Mephistopheles in 'active direct vision', and the lyrics of David Bowie ("Your Eyes" in Blackstar) it was not realised that people can create a watcher within their minds.

Western theorists seem to have missed out on autoscopic potential of the mirror neuron, or

McDermottian possibility that eyes are just as internalisable.

Until recently I had thought that the "eye of the Other" was internalised in an abstract, ineffable way. Japanese pictorial art is often represented from the perspective of "an eye apart," typically looking down, from the sky such as one can experience when playing Mariokart, Final Fantasy or other third person view Japanese video games (Masuda, et al., in preparation).

At the same time however, it also seems possible to model an eye within the self in a more concrete way, as the the first person view of self, such as may be represented by dogū, and the first person view that we have of their own brow nose and limbs. When I look at myself in the mirror I can see the noses and brow of the person on this side of the mirror. I can hold out my hand and caresses the surface of the mirror. Narcissus is portrayed attempting to scoop up his image from the surface of water, using his this-side-of-the-mirror hands.

In a sense perhaps the phonic equivalent of the nose and brow is the voice. I can narrate myself and when I do, when I call myself names, such as "Tim" or "I," the in that situation, there is likewise a "this side of the mirror" in the voice that expresses these names. Mead, and Derrida, rightly point out that hearing oneself speak (s'entendre parler in Derrida) introduces a believable duality. But I think that Nishida is right to point out (at least I think he is pointing out) that a similarly believable, or en-actable (kouiteki) duality exists in seeing. Since we can see our brow, and our nose(s), and often our hands, we see ourselves see. We do not even need a mirror to do so.

So, aware of the fact that self always presupposes and entails a self loving drama (with [less than/not?] one actor and two personae), in an attempt to rid themselves of their self-loving sin, the Japanese may have moved from destroying images of the self-person view in the act of destroying and burying dogū figurines, to destroying the phoneme in the act of a DONNGG, of a doutaku or joya no kane bell.

One can hear the sound of a bell on the

Japanese joya no kane wikipedia page and in this

Youtube Video.

Bibliography

McDermott, L. R. (1996). Self-representation in Upper Paleolithic female figurines. Current Anthropology, 37(2), 227–275.

websites.rcc.edu/herrera/files/2011/04/PREHISTORIC-Self-R...I have also argued that Japanese attempted to destroy inner ears (converting them to external ones) by

snapping their earrings. The more you love others the less you love yourself, and vice versa.